My research, part 1

Table of Contents

I study a particular type of solution to a particular geometric evolution equation. A geometric evolution equation describes how a mathematical object called a manifold (a simple line or a sphere is an example of a manifold) changes shape over time. What makes the evolution geometric is that the particular way in which the manifold changes depends on the shape, i.e. the geometry, of the manifold at any point in time.

This may sound complicated, and indeed it often is, but we can get a good feel for the topic by looking at some simple examples. One simple geometric evolution equation describes a type of process that everyone will be familiar with: the diffusion of heat through an object.

The heat equation

Suppose we have a wire1 that has been unevenly heated. We color the hot parts of the wire red, and the cold parts of the wire blue.

We can visualize the distribution of heat throughout the wire by a graph, so the higher the graph is above a point on the wire, the hotter the point on the wire is.

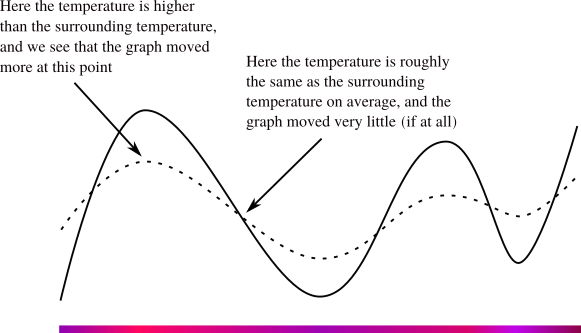

Now, if we allow time to pass, the heat will rapidly diffuse throughout the wire, and the graph will change correspondingly (we are mostly interested in how the graph changes). Notice that in some places on the wire, there were points with a lot of heat surrounded by areas with relatively little (as well as points of relatively low temperature compared to their surroundings). The temperature changed at these points much quicker than it did at points whose temperature was close, on average, to the temperature of the surrounding areas.

So it seems like a general rule for heat diffusion is that the greater the temperature differential with surrounding areas, the faster the diffusion. Not too complicated. It’s important to notice that temperature differential between a point and the surrounding areas is reflected in the geometry of the graph! Points like this show up in the graph as sharp spikes. So as the temperature diffuses over time, we see that the spikier parts of the graph diffuse away relatively fast. The mathematical way to identify spikiness of a graph is with the (spatial) second derivative. I won’t go into detail about derivatives, but it suffices to say that the magnitude of the second derivative is highest at the peaks and valleys of the graph, and lowest at the points in between.

This idea gives us the heat equation, the simplest model of heat diffusion. The equation looks like this:

$$\frac{\partial}{\partial t} f = \Delta f,$$

where $f$ is the function that describes whatever heat distribution the wire has (it’s the equation we would use to make the graph).

Don’t panic if you’re not familar with the notation! This equation says mathematically exactly what we observed before about how heat diffusion works.

The left hand side is the time derivative of $f$, which by definition describes how $f$ changes over time. The right hand side is the (spatial) second derivative of $f$, which as we remarked before just tells us how sharp the graph is at a given point. So if we interpret this equation into English, all it says is that the temperature of the wire is going to change over time, and if a point is surrounded by lower temperature, the temperature will decrease at a rate proportional to how much lower the surrounding temperature is (a corresponding statement holds for points surrounded by areas of higher temperature).

Geometric evolution equations

Now let’s forget about the wire and any physical interpretation of heat diffusion, and just think about the graph changing over time according to the heat equation. What we have is a 1-dimensional manifold (the line that forms the graph) with some geometry (the way that the line curves) and a partial differential equation telling us how the geometry of the manifold changes over time according to the geometry that it already has at a given time.

This is the idea of a geometric evolution equation. We start with a manifold that has some geometry2 to describe how it’s shaped. Then we have some differential equation that looks at how the manifold is shaped at a certain point, and tells the manifold to change over time in some way depending on that geometry. When the manifold moves according to one of these geometric evolution equations, we have a geometric flow. There are many different ways we can tell the manifold to move based on its geometry. These different flows have varying degrees of simplicity, usefulness, and physicality.

In general, manifolds can have any dimension. In higher dimensions, there are more directions in which a manifold can curve, which means that it is more complicated to describe the geometry of a manifold at a certain point. To describe the geometry, we use an object called a tensor field. A future post will be about abstract manifolds and the tensors that we use to describe their geometry.

The curve shortening flow

Before moving on to that topic, however, we will examine a geometric flow in a situation that is simple enough that we don’t need the language of manifolds and tensors to describe it (although we could talk about this situation in those terms if we were so inclined). The flow we will examine is called the curve shortening flow, and watching it in action might remind you of the diffusion of heat.

A cool interactive demonstration of the curve shortening flow can be found here and I recommend playing with this as you read the remainder of the post.

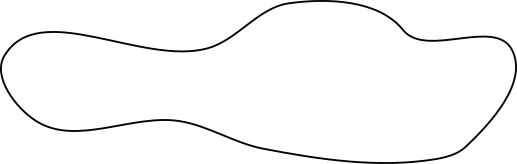

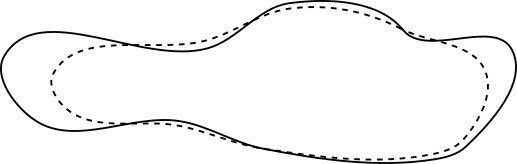

To define the curve shortening flow, start with a curve sitting in 2 dimensions:

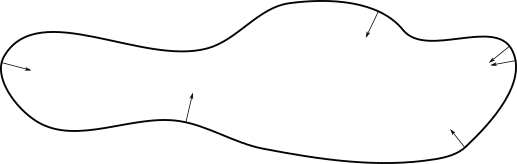

At each point on this curve, consider the direction that is perpendicular to the curve at that point:

(Only a few arrows are drawn to illustrate the principle, but at any point on the curve we could draw such an arrow.)

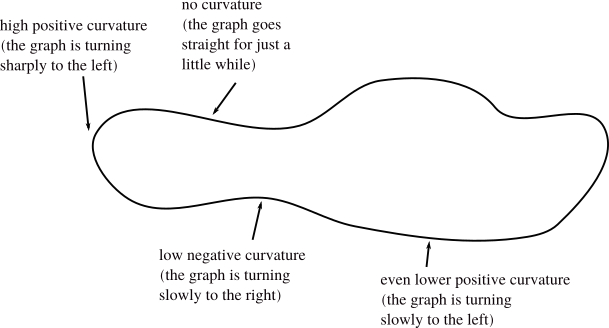

These arrows are called normal vectors. For a 1-dimensional curve sitting inside 2-dimensional space, the only geometric information available at a point is a single number describing the curvature at that point. If the curvature at a point is 0, it means that the curve looks like a flat line in a small area around that point. If the curvature is positive, it means that the curve is turning to the left from the perspective of someone moving around the curve counterclockwise. The curvature is negative at points where the curve is curving to the right from the same perspective. More positive or more negative curvatures mean that the curve is turning more sharply to the left or right (before we talked about “spikiness” of a graph, which is basically all we’re talking about here, but it’s in a more general context since this figure isn’t a graph of any function3).

So at every point along the curve, we have a normal vector that points in a certain direction, and we have a number. The curve shortening flow says that every point of the curve will move in the direction of the normal vector at a speed equal to the curvature at that point.

So if we consider the curve shortening flow applied to our curve from before, some points will move inwards quickly or slowly, and some will move outwards quickly or slowly.

Notice that some points move in the opposite direction of the normal vector. This is because the curvature is negative at those points, so they move in the direction of the normal vector with negative speed.

The differential equation to describe the curve shortening flow looks like this:

$$\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \gamma = \kappa \mathsf N.$$

Here $\gamma$ is the function that describes the curve, $\kappa$ is curvature, and $\mathsf N$ is the normal vector. This means that $\kappa \mathsf N$ is a vector that points in the direction of $\mathsf N$ and has length equal to $\kappa$: exactly the vector that should describe how points move under this flow. So this equation has a similar form as the heat equation. On the left hand side we have the time derivative of the curve. That is, the left hand side is referring to how the curve changes over time. The right hand side, as mentioned already, is a vector pointing perpendicularly to the curve with length equal to the curvature. So the equation says that the curve will change over time by moving in the normal direction with curvature speed.

What does mathematical research relating to such an equation look like? Good question! That is the subject of the next post.

Next post: mathematical research on curve shortening flow

Footnotes

For technical reasons, the wire is infinitely long and perfectly insulated. Not very reasonable physical assumptions, but a precise understanding of an oversimplified situation is very frequently much more valuable than a vague understanding of a real situation. ↩︎

In the case of the graph, we can see the geometry by calculating the second derivative, or just by looking at the shape of the graph, since it’s drawn out for us. For an abstract manifold, we don’t have this luxury; in general a manifold is not sitting inside a larger space the way that the graph sits inside the larger space of the plane on which the graph is drawn. We need other tools to describe the geometry of abstract manifolds. This is where the metric tensor comes in. Hopefully I’ll have another post on this topic soon. ↩︎

However, this figure does have an important property that it is locally a graph! If you choose a point on the curve and only look at a small region of the curve around that point, you may notice that this region could be described using a graph of some function. However, since there isn’t a single way to choose this function, this notion of curvature is genuinely different from the second derivative of a graph (but it’s analogous)! ↩︎